The Nuanetsi, In the African Bush

Ground Hog Day

It was my third “first day” in Zimbabwe. Each day was so unique that it felt like starting over. I woke at 5:00 a.m. and laid for a while, enjoying the darkness, anticipating the day. A Hemingway quote floated through my mind; “I never knew of a morning in Africa when I woke up that I was not happy.” I get you, Ernest. At 5:15 on the mark, the melodic voice of the camp steward streamed through my open window; “Good morning, Sir.” “Good morning to you, too!” and I truly meant it. Stumbling about, I found the right combination of green and brown, or maybe a touch of woodland camo today. I slipped on the Kudu leather gaiters, covering my socks instead of leaving a reveal, as Peter had been so kind to point out. Stepping from the door of my hut, I scanned my flashlight back and forth. This “little tip” came from my PH, who said he always checks for snakes, lions, and leopards before heading into the dark. It was a nice tip, and I feel fortunate not to have learned it the hard way. The trip to the open-air dining area was brief, with baboons, monkeys, warthog, and waterbuck grazing just feet from the cobblestone path. Ahh, good! The lions and leopards will get to them first. A fire was already ablaze when I stepped up to the spacious deck. This was the perfect place to soak in the morning twilight as it reflects off the Mwenezi River; the crocodile-infested Mwenezi River. Gazing upward, I noted three bright stars in a row—the belt of Orion. There he was, sword shining at his side, his bow tightly drawn.

Under the Ironwood Tree

My PH, the renowned Lou Hallamore, was already seated at the table, working over a bowl of grits. Lou looked my way as I pointed to the sky; “It’s Orion, Orion the Hunter!” He returned a gritty smile, and I will swear to this day that I saw a glint in his eye. No words were necessary as our sign showed brightly overhead. This was the day; we both knew it. My first experience with Orion was 30 years before, from the edge of the Grand Canyon at about 2:00 in the morning. My backpacking friend, Allan, pointed it out. Whenever I see Orion, I think of that moment, standing in a foot of fresh snow, pondering the trail that could have easily taken our lives with one misstep. Now, this moment in Africa will share that place in my memory. “Magic,” as they say in Zimbabwe. It’s all magic.

The actual “Day One” began with a trip to the range, and I felt confident with my Ruger Guide Gun. From the bench, it will consistently place groups less than one inch. I chose this rifle because it had specific features that seemed important in the African bush. The three-position safety is ideal as I would find myself regularly ejecting a live round before storing the rifle back in the Safari vehicle. Barrel-mounted sights are there in case something happens to the scope, and the stainless finish is perfect for the conditions. The Mauser action is an African standard. My first round hit ½” right of center on the 100-yard target. “No need for another… let’s go!” But first I needed one more lesson.

The Machine

The idea of shooting from “the sticks” was foreign to me, but this lesson would be critical to my success. The tracker would learn how to place the sticks for me, as my height and how I brace my stance make a difference; the process must be perfected and executed quickly. With the forestock of my rifle planted in the saddle of the sticks, the tracker stood to my right, bending over so that I could rest my elbow on his shoulder. It seemed awkward at first, but when performed correctly, it was rock-solid, with not the slightest waver in the crosshairs. This lesson was succinct, and once it was completed to Lou’s satisfaction, we loaded into the Landcruiser.

The Machine

Our team consisted of two trackers, Clement and Takesure. Clement carried the shooting sticks while Takesure handled the .338 backup rifle. Amato, the father of Takesure, was Lous’s driver. Amato, always in radio contact with Lou, would be there to re-supply or find us when we were buried deep in the bush. His navigational skills are uncanny; the GPS is in his head. These men have been with Lou for over twenty years and have shared many hunts. Like family, they rely on each other for life and limb. Speaking of family, Amato, a farmer and man of some stature in his village, has two wives, sisters in fact. A testament to the need for pragmatism vs. propriety in rural Zimbabwe. Perfect joined us as well. He was our Nuanetsi game scout and an enthusiastic man who, with a tap on my shoulder, would help guide my eyes to the target. Of course, the PH, Lou Hallamore, and I rounded out the team. The feel of a classic safari was setting in for an American hunter surrounded by top-notch professionals.

We moved out for the first time, and I would soon see how the “machine” works. It is a finely tuned system, and I was part of it. In fact, the most essential part of the machine is the hunter, the trigger man; success or failure lies on the tip of his finger, so our gears need to mesh well. The machine works like this: Bang, bang, bang on the roof of the ‘Cruiser. Game has been spotted! The truck stops as I step from the left side door. Clement is already on the ground, either setting up the sticks for a shot or starting to track. The Ruger is hanging from Takesure’s hand, stock down. I grab it, rack in a shell, confirm the safety position, and start moving. If the sticks are already set, I move quickly into position for a potential shot. If not, our troop proceeds through the bush single file in this order: Clement is in the first spot, followed by Takesure with the backup rifle, Lou, myself, and bringing up the rear is Perfect. Amato remains at the truck, waiting for radio communication. Our group’s profile is kept to a minimum by walking in a single file, and of course, I would key off of Lou and his movements. Voice commands are few, as most communications are by hand signals. When the potential for a shot comes into play, Lou waves me forward with a little wiggle of his hand from behind his back. Now, behind Takesure, I know things are about to get real. Anticipation increases with every step, every motion, and especially the reactions of the trackers. When in the third position, I focus on Takesure. His eyes are a dead giveaway to what is happening and all I did wrong. Step on a branch, clear my throat, Takesure’s eyes would cut through me like a laser, surprised that I could be so careless. He had no idea how green I was, but I learned quickly, and Takesure was my silent teacher.

The moment Takesure steps aside, I know it is time for my cameo. All eyes are on me as I approach the sticks, and the anticipation I carried for minutes or hours has turned into intense focus. I have seconds, just two or three, maybe. It is incredible how the mind can juggle several competing ideas simultaneously. Should I take the shot? The sticks are down, so does that suggest the shot is good? What does my PH think? Too many branches? Too long? Do I want this animal for my trophy? Those few seconds culminate hours of tracking, glassing, and strategizing. Yes, I am front and center stage. No pressure, though, right? If I wait one second too long, the opportunity is missed, perhaps never to be found again. This is something that every hunter must consider in advance, whether in Africa or anywhere else. I learned that my attention must remain intense for hours if necessary, and these questions must be answered before they are posed.

This process would be repeated numerous times over the first two days as we maneuvered for a shot on Kudu, Zebra, or Impala, each time quicker and smoother. It felt good, and I sensed that my team felt good about it, too. Though we didn’t put anything “in the salt,” it’s fair to say that I was elated; I felt like an African hunter, and we were now a well-oiled machine. We had many occasions to turn “the machine” loose into the bush, but I was still on my initial African high, and I collected dozens of photos and videos of African wildlife during the first two days. Likewise, our second cameraman, Dean, hung with us on day one, intent on capturing my delight. Honestly, hunting was almost secondary to me as I viewed creatures I had only seen in magazines or on television. The experience was euphoric, and it would be days before the sight of a giraffe or any other beasts we saw came even close to approaching mundane.

The giraffe came in all sizes, but the very large ones are a magnificent sight. When running at a gallop, they seemed to defy the laws of physics, moving in slow motion when, in reality, they could easily exceed 30 miles per hour. Sometimes, only their heads were visible above the Acacia trees as they ran away; the appearance of a disembodied giraffe head flying through the treetops was quite entertaining. The Impala wandered about in herds of twenty or thirty. At full speed, their stride seemed to be 30 to 40 feet, appearing only as a blur. Chevrolet should have named the Corvette “Impala”; it would have been more fitting. Troops of baboons were everywhere, and waterbuck, bushbuck, and warthogs meandered about, apparently aware that we were not hunting them…yet.

Elephants at the Watering Hole

And then the elephants- we saw many, including a group of five, running across the road at top speed. Clearly, it was a prime example of being in the right place at the right time, but I imagined the carnage had we been a mere ten seconds further down the road. Each sighting was similar to a religious experience: a soundless six-ton deity floating through the bush like an apparition. Their focus was entirely upon us as the snorkel-like trunk and massive ears sampled the incoming data for processing by a 12-pound brain. I was thoroughly aware that our vehicle provided little protection from an agitated pachyderm. Days prior, in an area just south of here, a safari vehicle was shredded by an angry elephant, killing one of the occupants. The sight of an elephant could never be mundane; I felt my heart pounding each time Lou took us in as close as possible. Those were the moments that I knew my life was truly in his hands. But like the elephant, Lou’s central processor also collected data from the elephant’s behavior and thus knew exactly when it was time to bug out.

Lou also discussed another species of elephant present in Zimbabwe. One that is unknown to most, except those who hunt here. The ones we had seen were regular African elephants (Loxodonta Africana). But there was another, a species we never saw. These ones are responsible for the downed Mopane trees that regularly blocked the road as we drove about. Lou referred to this species with his loose “Latin” translation as “Fricking Elephants.” I do not know the actual English pronunciation, but it is Loxodonta Fututus in Latin. Apparently, this is a sub-species that has evolved solely to torment hunters. Look it up.

Happiness is a Warm Gun

Day three began as the others. While we rumbled along the dirt trails, my mind lapsed as I stared forward through the ‘Cruiser’s windshield. Unexpectedly, we stopped. No “bang, bang, bang” on the side of the Landcruiser; this was obviously Lou’s call. Lou stepped out, and in a quandary, I quickly followed. My Ruger was already hanging from Takesure’s hand, and the shooting sticks were up! I grabbed my rifle, racked in a shell, checked my safety, and looked to Lou while he silently pointed down range, then said, “Shoot that damn thing!” About one hundred yards away, a Black-Backed Jackal meandered about, although I had no idea what this dog-like creature was. I dropped my stock into the saddle of the sticks, steadied up, and pulled the trigger. The whole process took about six seconds, from exiting the truck to the trigger pull. Yep, that’s a well-oiled machine!

The Jackel

But, the Jackal took off at full speed. What happened? I could not have missed, but Lou thought I hit low. After about a twenty-minute tracking session, we found him, expired, in an old antbear excavation. The bullet had pierced through both lungs exactly at my point of aim. Nothing’s for certain in Africa, except that even the little animals are tough. However, we had one “in the salt,” which was an appropriate beginning for a new hunter.

Looking back on our first kill, I now understand some of the profound wisdom of a man who has spent decades in the bush on both two and four-legged safari. At the time, I thought the jackal pelt wouldn’t make a particularly fine trophy; it wouldn’t be hung over the fireplace or sprawled out on the floor. I had no genuine desire to shoot that Jackal, but the moment was not just for me. As a highly experienced leader of men, the former Master Seargent understood that we needed success, any success, to keep the edge and cohesiveness that we spent days perfecting. And that’s why he made this call. The machine isn’t proven with a few laps on the track. We needed to get into the race!

We stood around the antbear hole, everyone smiling and laughing. The trackers exchanged comments in the Shona language. Indeed, we had bagged something we needed and would need for the rest of the Safari. It wasn’t about the jackal. It was all about the team. And now I know the jackal pelt will make a fine trophy that will hold my memories of a legendary African PH and those moments with “my machine” at the Antbear hole.

Zebra, with a short “e.”

Yes, Zebra is pronounced in Zimbabwe with a short “e,” but try not to sound pretentious when you utter the word. Not long after the jackal hunt, a herd of zebra was seen crossing the road. I am sure they cared not what we called them, just that we were there, rifle in hand. We moved the ‘Cruiser into position about 100 yards from where they crossed in hopes of flanking the herd while staying in cover. The “machine” exited the truck and proceeded briskly through the bush, following the anticipated direction of the herd. Takesure and Clement widened the gap between us as they moved forward with a quicker gate. Within just a few minutes, they stopped, turned, and eagerly waved me up. There were no words, just an insistent finger pointing forward and to our left. Shaking my head to and fro, I signaled my confusion. I could see no Zebra! Clement, palms facing the ground, made a sweeping downward motion. Descending to my knees, I saw the herd stallion through a small gap under the bush as he stared back in our direction. The sticks were now in place, so I knelt low and bent to the left, twisting my old frame to its limit. The zebra stood still in a quartering position, and I knew time was limited. This is not the shot I had anticipated! Aiming to the right of the left shoulder, I tried to visualize the low-lying vitals of a zebra. Squeeze, boom! The zebra left us in a cloud of dust.

Zebra Trophy

I hoped that we would find our quarry silently expired somewhere nearby. That was not to be the case. However, a bright blood trail departed from the last known location. Lou informed me that at the next available chance, I must put another round in him; we had to slow him down. The trackers moved out ahead, following only hoof prints with sporadic blood drops confirming that we were on the right path. I felt a little low two miles later, but the trackers were confident. As we crossed a road, Lou radioed Amato, who minutes later met us with the truck and fresh water. We refilled our canteens and continued on. I noticed the blood drops were more frequent; was he slowing down? Or did our pause for water create some relief for the zebra as well? Fresh scat proved we were on the right trail, and after an hour or so, we spotted him prancing about behind a grove of trees before he spurted away toward the thick brush. He looked healthy. The disposition of the team quickly changed. With the day waning, we might lose him if he makes it into the heavy bush! But we did catch up. With our trackers just ahead of me, I took the initiative and stepped quickly forward and far to the left to gain an angle for a kill shot as Lou and the team watched. A thick grove of brush blocked my bullet’s path once again, but there was nothing to lose by lighting off another ’06 round. Aiming high to avoid the dense brush, a reverberating boom signaled what I hoped would finish our chase. Through the lens of the scope, I could see that the round had made an impact as the zebra jerked and twisted: It was a hit! Astonishingly, he galloped off again. Without words, the machine fell quickly into line again and moved out at a fast pace, this time to a mere 50 yards, where we found him standing in a grove of small trees. A quick free-hand shot into the vitals ended this hours-long saga.

Smiles, cheers, and handshakes were exchanged as the team celebrated a well-earned victory. Impulsively, I gave Clement a big bear hug. His performance left me ecstatic and amazed. Indeed, he and Takesure were the star players on this hunt. Once we extracted the stallion from his final resting place, I found the location of my second shot through brush. It was a high hit but good enough to slow him down for the final approach. According to my GPS, we covered almost four miles in 2-1/2 hours. I had not expected it to go this way, but success supplanted all else. Following the trackers was mind-boggling since every square foot of the ground in this area is covered with tracks. I will never know how they could follow one animal that distance unless I learn to speak Shona and or get reborn in Zimbabwe.

The realization of our success had sunk in, and I turned to Lou and offered a truly honest apology for our lengthy tracking session. It may have seemed insincere since I could not wipe the beaming smile from my face. Though every hunter hopes his quarry will be DRT (dead right there) after the first shot, I truly enjoyed tracking that Zebra for miles. It is an experience that every African hunter must have! The look on Lou’s face was hard to read, but I won’t forget it. I guess he thought that I had lost a few of my marbles. Which is fine; the trackers could find those, too. Surely, he knew what he signed up for when he offered to guide a rookie into the bush. With our trophy loaded in the back of the Landcruiser, we headed back to camp. The African sunset burned through the day's dust, lighting the horizon in red, pink, and yellow shades. In the back of the ‘Cruiser, our crew bantered about, their conversation accompanied by regular laughter. Lou and I shared a couple of “cold ones.” We were all satisfied; our day was complete.

Zebra in the Bush

My mind reflected back on the day, and I surmised a solution to the long-debated theories on the zebra stripes. My final photo of the zebra was taken in the bush where he fell. Laying still, it was hard to discern that a zebra was there. It seems evident that the thin vertical trees that proliferate in certain areas are the perfect cover for a zebra, especially when they are standing still. Our eyes would have been useless without our trackers bringing us within a few feet of the zebra each time.

Back at camp, a quick shower and off to “happy hour,” where hunters and PHs congregate to discuss the day's events before dinner. Lou and I visited the skinner's pit where our zebra was already hanging. We observed that though my first shot placement was as planned, I had failed to consider the upward trajectory of the bullet, thus just grazing the topside of the lung on its passage through to the high right side of the animal. I estimated that the angle through the zebra was about 25 degrees from horizontal. That angle suggests that I was much closer than I thought. These observations provided an essential insight that should be requisite upon any kill. On a side note, it is advisable never to visit the skinner's pit before dinner. However, a shot of Scotch did manage to kill the lingering contamination of my palate.

Though my success was not much to share with the dangerous game fellows, hearty congratulations were offered by all. After all, they were once in my shoes. Stories were then recounted, including size, location, techniques, failures, and successes. As part of a timeless Safari tradition, we shared handshakes, salutes, heckles, and laughter as the action was replayed in full color. But on this evening, happy hour took a somber turn as we learned that one of the hunters had wounded a leopard during the previous night’s hunt. Suddenly, our four-mile Zebra trek seemed routine. Three PH’s would head out in the morning to finish the job. I approached Peter, one of the PH’s, and in an expectedly naïve fashion, I commented that it sounded like he was in for some excitement. In a friendly but typically blunt Zimbabwean fashion, he replied, “It is not exciting; one of us may end up injured or worse.” He was serious. Stories of wounded leopard hunts often end up with someone in the hospital. The database of such events is sufficient to provide a mathematical estimation: 100 stitches per second, and hope the leopard misses the vital arteries. But that is a story for elsewhere in this book.

An unfortunate set of circumstances contributed significantly to the wounding of the leopard, as any hunter would understand. Hershell’s rifle was stuck in transit somewhere between Jo’berg and Bulawayo. Soon after we arrived, a proper leopard had already been found for Hershell’s hunt. This is not a minor undertaking, as the PH’s baited at least six locations, days in advance of our arrival and checked the game cameras daily. Every leopard in this conservancy is documented down to the pattern of spots on its fur to determine its age and suitability for harvesting. With careful study of the camera images and a large portion of hard work, they had found the ideal candidate. The day of the hunt arrived, and the one essential piece of equipment needed to consummate a very expensive hunt was missing: the rifle. This hunt had to begin immediately before the baits were depleted, or they would need to start from scratch; harvesting zebra bait and setting cameras once again. So, a loaner rifle was used for the hunt and that would prove to be one variable too many.

With the discussions and celebration still running-on our table is being prepared. Dinner was always an elaborate affair. Safari attire, properly pressed by our generous staff, is the order of the evening. Meals always began with a sincere prayer of thanks for the opportunity to experience God’s great creation and for the safety of our hunters. Excellent South African wine made the rounds, filling our crystal stemware. The bottles would always start with the ladies (Tanya and Michaela) and magically ended up with them as well. I am not sure if that is tradition or a carefully orchestrated plan. Linen napkins neatly adorned our porcelain plates, sometimes folded into origami-style patterns of birds. Our salads and vegetables were grown nearby and harvested daily. My favorite dish was the Zebra Schnitzel, likely sourced from the backstrap of my Zebra trophy.

Dinner

Humbled Again

Having collected my first trophies, it was time to move on to the next opportunity. There are hundreds if not a few thousand Impala on the Nuanetsi. It should be easy to find a good trophy. Well, a needle in a haystack is easy to find, too, if you have a magnet. We didn’t have an Impala magnet, but we had five good sets of eyes; five and a half, counting me. Once we found a herd, we ambled slowly further into the bush, hoping to get the glass on them. If the trackers spotted an ideal candidate, we could set up a shot.

Frickin Elephants

Otherwise, we moved directly to the spot where it was last seen. From there, the tracking begins. I kept in mind that they are focusing on one animal from an entire herd of twenty to thirty, including other males. As I watched trackers perform their magic, we had sighted a beautiful buck at about 75 yards within the hour. The intervening brush made this broadside shot sketchy. I took it anyway, knowing that there was no way I could miss it. After an hour of tracking, no blood was found, so my shot was deemed a miss. Africa wins this round.

The next day, it was “rinse and repeat.” Rinse away the failure of yesterday and repeat the same technique. After several hours of scouting, we again found an ideal candidate. The buck was among his herd at about 100 yards. Lou pointed him out, standing right next to another buck. Again, this was no broadside textbook shot. A few small branches extended into view. Another buck was standing so close it was hard to discern where one began and the other ended. The faint variations in hair color were enough. With a direct bead on his shoulder, I squeezed off an easy shot. Poof! The whole herd scampered, and the tracking began… again.

Impala

Within a short distance, the trackers picked up blood, and soon after that, they found intestinal contents. This simply meant that my shot had been deflected way low into the viscera of the buck. Another branch, it seems. This tracking session would extend to four hours as we followed the wounded animal around and around. Numerous times, we saw him moving briskly through the brush, evading us time and time again. Twice, we would lose the track. The trackers would then start moving in wider and wider circles until the track was “cut” again. It was beautiful to watch a work of art being inscribed on the ground by movement and observation. Finally, we found him, spent, standing broadside next to a Mopane tree. The white flag was up, and a final shot put him down. I cannot say I was happy but relieved that the Impala’s suffering was over and our Trophy had been collected. I was humbled…again. It was time for some introspection before we moved on to our next target.

Kudu with a Side of African Jack

Kudus are browsers and are often found among leafy brush and trees. The shady tree-lined gullies and river edges are ideal habitats. They are highly intelligent animals, and hunting them reminded me so much of pursuing elk in Colorado's high country. Like elk, their noses are their best weapon. This would be a four-day adventure as we found many Kudu bulls, but most were not trophy quality. Late in the afternoon, on our second day in Kudu Country, we happened upon a beautiful bull. By staying low and watching the wind, we were able to stalk within fifty yards as he was peering back in our direction, partially obscured by branches. No shot; I had learned my lesson. The first move goes to the Kudu, as our pawns fall to the board. But it was not over, for he seemed to need to keep eye contact. This action reminded me of a common elk tactic. We tried several times with flanking maneuvers, using the brush as cover and always cautious to watch the wind. As I was told, once you are winded, you might as well head back to the truck. You are now owned.

The sticks were set, then moved, then set again as opportunities to shoot emerged quickly and disappeared quicker. A wild animal was completely outsmarting us….and I loved it! This chessboard dance went on for more than an hour. It finally occurred to me that he was pushing us… upwind! By the time we realized his plan, it was “check and mate.” Thank you, Mr. Kudu, for a fine game as I smiled all the way back to camp. At camp, happy hour was on, and I sat with Lou as we discussed the plan for the next day, enjoying a lively fire and some scotch on the rocks. A change in tactics was formulated.

For day three of our Kudu hunt, we decided that finesse might be the way to achieve victory over our Kudu adversary. So, in the morning, we parked near a pond in the midst of Kudu Country… and sat. Sitting is my least favorite way of hunting, but we weren’t setting the rules for this hunt. Two hours went by. First, the Impala showed up, followed by some Kudu cows. Things were looking good, and as we had hoped, the first of three Kudu bulls showed up, with the others slowly straggling in. We had spread out so that all angles could be covered. Lou covered the right flank, and I was in the middle, standing close to a tree. A downed tree on the left flank obscured Takesure, Clement, and Perfect. Judging by their reactions it was apparent that none of my hunting partners had a visual on the Kudu. So, looking toward the trackers, I carefully got their attention. With my left hand, I drew an upward rising spiral signifying a Kudu bull, an impromptu hand signal, and it worked! Clement dropped low and made his way towards my position. After a quick assessment, he moved carefully towards Lou’s position on the right, which was obviously for a discussion on strategy. For a moment, I was drawn back to my childhood days when I played army with my buddies in the local park. Here we were, five grown men, playing “Army” with an “enemy” that was far superior.

Lou (left) and David Bartlett (middle) sit for an interview with African Jack (right).

One of Kudu met our criteria, a likely 50 incher. But what to do? Protocols prevented us from shooting at the water hole, and there was no shot anyway due to the heavy brush. So, ducking low, we quietly did a far end-run around the left side of the pond, hoping to intercept them upon their departure. And we succeeded, but they stayed buried in the brush, looking back in our direction. Approaching through the brush and thickets was impossible. After working on this scenario for a couple of hours, we admitted defeat. Overall, it was a good plan, but it needed some improvements. We departed, scouting and glassing our way back to camp. Back at camp we made some adjustments to our strategy; instead of intercepting them at or coming from the pond, we would attempt to intercept them on the way in. With a few calculations of Kudu walking speed and time of day, we surmised that we needed to be planted just off the road by 8:30 A.M.

The next morning, we left early, joined by African Jack as our cameraman. Being a true “run and gun” cameraman, A.J. has a way of keeping things live, real live, and it was great to have him along. Jack speaks in a wonderfully resonant, bass-baritone voice, and even at normal volume, he cannot be missed, whether across the room or the river. His thick South African accent adds an ambiance that blends naturally with the safari atmosphere. A man of indomitable energy, he does not know the clock but survives on “cat naps,” always ready to document the next adventure. Only the dead could not light up in his presence.

It was a two-hour drive to Kudu Country, and we were running close. After about an hour and a half into the trip, a bang, bang, bang on the side of the cab signaled us to stop. I grabbed my earmuffs and opened the door for the awaiting rifle. Here we go; the machine is in motion! However, this time, I was wrong. Jack needed a potty stop…real bad. As the two-minute mark passed, I contemplated the size of Jack’s bladder. Is he superhuman or part animal? Probably both. I was about to jump out and berate our favorite cameraman when he loaded back up. With a smile, he apologized for his three-beer breakfast. Now I was really agitated. Would we run out of Zambezi before the day was over?!

We were a bit behind but closing in. Within a few hundred yards of our destination, we spotted a Kudu ahead of us, quartering forward from our left through the trees. It was our Kudu! It was him. The Kudu paid us no attention; his mind was probably fixated on a cool drink at the pond. The Landcruiser stopped, and the sticks went up! Crouching, I moved slowly forward, planting the Ruger on the saddle of the sticks, and already dialed down to two-power on the scope, I waited motionless. Our Kudu casually crossed the road at about 75 yards as I listened for permission to shoot. Lou’s frustration came through when he quietly ordered me to “Smoke him!”. I understood the command, but in the few milliseconds before my brain gave my finger the order to press the trigger, my lips did something strange; they cracked a smile, but smiles sometimes precede laughs. So, I expedited the process, ordering my right index finger to unleash the 200-grain Northfork. It did its job well by sending the projectile into the vital zone and passing through the lungs and the heart. The Kudu ran into the woods on the right side. Oh no! Not again, as I lost track of him in the bush. Seconds later, Takesure yelled, “He’s down!” Since I don’t speak Shona, I discerned from the smiles and cheers that we had succeeded. The Kudu bull lay lifeless, not 25 yards from the road's edge. Lying on a slight slope, a river of blood spilled from his open mouth, testifying to the devastating impact of the semi-spitzer bullet. I was pleased; this was the clean kill I had hoped for and the trophy we had long sought.

Kudu

I approached “our” trophy, and the memories of the days on the quest for this Kudu, the miles we traversed looking for wounded Impala and Zebra, drained out of me in a flood; those events to be replaced by this hunt. My missteps, poorly placed shots, and the hours following the wounded were necessary to earn this success. The abrasive nature of Africa had honed me for this moment. With my heart pounding, an immutable smile dressed my sunburnt face. I thought of Lou’s words; “Smoke him.” A term of art in the military world; did these moments unravel something profound inside him as well. Perhaps he just needed me to know that my actions must be unequivocal.

Jack’s extensive photo session was completed, so we prepared to load the beast for our trip back to camp. African Jack walked up and offered the following observation; “Good thing we stopped so that I could dangle my ding-a-ling, huh?” I had to admit that he was right. We would have driven right past the Kudu if we had arrived two minutes earlier. Fortunately, Jack had stocked plenty of Zambezi in the cooler so we could celebrate our way back to camp. The next toast is for you, Jack. And as it always is in Zimbabwe…Magic, African Jack style this time.

Lou and I

A Day Alone

I had completed ten days of hunting. My bag was full, and Lou had departed. However, I looked forward to hunting with Tanya Blake for two days. At 29 years of age, Tanya has already made a name for herself. A soft-spoken blonde, she appears unassuming and thoroughly incongruent with the stereotypical idea of an African PH. But her exploits are well documented as they were earlier during our hunt. She was the front “man” during the pursuit of the wounded leopard. I saw the video as she dispatched the charging leopard at a mere ten feet! Later, she spoke of it in camp with an occasional smile or casual laugh, the other PH’s and hunters hanging on her every word. What else can you expect from a woman who grew up in the bush, a third-generation African professional hunter? Of course, I wanted to hunt with her.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. Her special skills were needed to track a wounded buffalo. I arose late, dressed well, and enjoyed an empty camp, unsure what to do for the next ten hours. Hiking was not an option, as only a fool would go out alone in this area. Yes, I can state that with authority. Just a few days earlier, our ‘Cruiser was charged by an angry lion intent on protecting his fresh giraffe meat, which was less than a mile away! These same lions had been meandering near camp for a few days, and their occasional roars were a very audible sign of territorial possession. So, I took repose on a lounge by the pool, contemplating the need for a loaded rifle. In my first hours on the deck, I saw no one else in camp, and a firearm's comfort became more than just a passing thought. While gazing about, I heard a loud bird call, and looking up, I noticed two Fish Eagles circling the camp. I think they were saying, “Hey, what about us?” Yes, bird watching! I headed to my hut to retrieve the image-stabilizing binoculars I had bought for the trip. While there, I stared at my Ruger for a bit but decided to leave it behind, even with scenes from the movie “The Ghost and the Darkness” replayed in my mind. The Sig Sauer 12x bino’s are a game changer. They are so good that, after Peter played with them for a while, he ordered a pair for himself. Turning toward the river, I could see many bird species, but I could not identify them.

Looking to Collect Some Rent

The solution arrived about noon as Micheala sauntered over from her hut. “Would you like a refreshment?” she asked. “Of course!” Since I’d already had enough of the “freshly mixed” African O.J., I suggested a Zambeze, four percenter, as the day was still early. Moments later, as I was glassing along the river, Micheala slipped a cold one into my cargo pocket. Let the bird-watching begin! She knew every bird, and we identified many. The Pied Kingfishers will entertain as they hover precisely over the river, not varying an inch. When ready, they will assume the dive-bombing position, wings folded, rocketing into the river like a missile. The fish eagles are very similar in stature to Bald Eagles and regularly reappeared to draw our attention. We looked at the wading birds, including maribou and saddle bill storks. There were other wading birds. I don’t remember their names, but I thought they were poor fools with crocodiles slowly approaching their positions. And the call of a particular Cuckoo bird was ever-present. The neurotic repetition of its song drove me crazy while sitting in the bush. They repeated this quintessential African query; “Where’s the leopard?” “Where’s the leopard?” over and over and over. I supposed I would be neurotic, too, if I had to live in the bush with leopards. Truly, this is a birdwatcher’s paradise, right from the deck of our camp.

Saddle-billed Stork

Fish Eagle

Michaela stepped away to address her essential business, and I moved to escape the now-risen sun. I selected a seat in the shade that was cast by a giant Black Ironwood tree (Olea capensis), also known as the Ironwood Olive, due to the succulent ovoid fruits that the monkeys enjoy so much. Here, sitting in a ring of chairs, our hunters enjoyed many lively conversations at the fire pit. Today, I had it mostly myself. The day's peace was regularly interrupted by the echo of olive pits striking the deck as the monkeys cast them about. I chose a seat to view the river while avoiding the hail of olive pits. Soon, a baboon scampered in from out of nowhere and made his way up the tree as if the tree was horizontal. It was a bit of a surprise, raising the hairs on the back of my neck. Though dozens of them meandered about the camp, they typically avoided our activities as long as we remained similarly disposed.

Cape baboons are not inconsequential denizens in these wild environs. With canine teeth approaching three inches long and dog-like muzzles, an encounter would be far worse than that with an angry shepherd. My apprehension increased as I found myself the target of olive pits while the baboon grazed directly above my chair. So, I moved to a chair across from the fire ring. Defying all odds, the pits were once again dropping about me, bouncing off the rim of my hat, or deflecting off my shoulders. The message was clear, “Move along; you are not welcome at my table.” I removed myself to the previous spot at the edge of the deck, a little disturbed by this unwelcomed communication from a wild animal. The Ruger once again entered my thoughts. Perhaps he somehow knew that since my arrival, I intended to put one of his kind in the crosshairs. I had watched the baboons and how they take to bipedal travel when convenient. It is hard to deny their somewhat related genetics, but I wondered if he held the sixth sense that our species has mostly lost. At that moment, I decided a baboon skull would look “right proper” in my office. Maybe they can read our minds, so it was time to put that to the test.

The Deck

My afternoon on the deck progressed, and more Crocs started moving about—dozens of them with some youngsters lounging about on the islands. The big ones looked like logs swept from the banks after a gully washer. Directing my binoculars into the distance, I saw Bush Buck, Kudu, Impala, and more. With refreshments and snacks aplenty, I continued, slowly descending into a state of bliss. I realized I didn’t need to go anywhere because I was already there.

The Zimbabweans

As most of us go about our day-to-day routine back in our American homes, it is interesting to consider that these men and women will spend decades in the bush, often pursuing dangerous game. What’s it like? Who are these people?

Zimbabwe was borne out of conflict from the former Country of Rhodesia. This is not ancient history, as the experience is still carried in the hearts of some of those I met, especially Lou. A visitor to Zimbabwe should at least have a basic knowledge of how Zimbabwe came to be. To be frank, the former Rhodesia was a successful First World country before about 1980. But what I encountered is thoroughly a Third World country. The descendants of the former British colonists once numbered 300,000. Still a minority by any standard, the number is now closer to 30,000. It was tenuous ground to break, but I did ask Michaela, Lou, and others: What is it like…living…here? The answer was often an ecstatic: “We love our country!” or “This is my home.” Could it be the awesome beauty, the fantastic hunting, or the historical connections that allow them to ignore the razor wire, electric fences, the failing infrastructure in the cities, and the regular police checkpoints? Have they been afflicted by the boiling frog syndrome or perhaps a Country-wide version of the Stockholm syndrome? I don’t know, but I was not so naïve as to dig any further. Carpe diem! The past is where it belongs.

The perspective endowed by age and experience is essential to understand history. Lou, Peter, and I spent some time discussing current and past affairs. It is clear that the tragic end of Rhodesia at the hands of Communists, supported by an international coalition of liberal ideologues, was a massive historic mistake. No person in Zimbabwe is better off as a result except for the extravagantly corrupt leadership of the Country. Interestingly, we all came to the same conclusion regarding the good ole U.S. of A. In 2024, our Country is already well on its way to Zimbabwe status, but it is just being done at a much slower burn rate. As part of the standard communist program, no black person in Zimbabwe is allowed to possess a firearm. Those possessed by the PH and their clientele are heavily regulated and tracked. For the would-be hunter, be prepared with all of your firearm paperwork and ensure that there is not a single error thereupon. At the end of the hunt, I offered Lou my last two boxes of ammunition. He declined, informing me that every cartridge must be accounted for and registered to a particular firearm. Prison time is the consequence of failure to do so. However, it would appear that the few guns owned by the registered PHs are not a threat, likely due to the vast economic windfall that Safari hunting provides to the rural population of Zimbabwe.

There are other uses for firearms in Zimbabwe. Poaching is still a problem in rural areas because of the international trade in animal parts, especially ivory. I was told stories of encounters that PHs have had with poachers. Fortunately for them, an accurate bolt action rifle has more than once won the day against those wielding rifles chambered in 7.62x39. Lou also expounded upon the treatment of poachers once they are captured. Those stories cannot be reproduced in print, but it is fair to say that Zimbabwe's justice is swift and brutal; no warrants or lengthy trials are needed. The only requisite item is a well-sealed body bag.

For the uninitiated, the Zimbabwean accent is often confused with that of the Australian. With a little exposure, I see that the differences are more than nuanced. The Zimbabwean man’s speech is somewhat staccato with guttural lows that seem perfectly adapted for penetrating the thick African bush. The ladies, on the other hand, speak with something closer to a proper English accent. They sound elegant, even exotic, as long vowels are rare and words often finish with a flourish. One thing is for certain: whatever is said is done with a smile.

Entertainment Committee

Most of the hunters in our camp retired early, but I could not sleep. I occasionally stayed up late to enjoy the party that went on until the wee hours, aided by a steady low dose of adrenalin and a touch of whiskey. Truly, I subsisted on about five hours a night for two weeks. The Africans- our cameramen African Jack and Dean, Michaela, Tanya, and others- would be up late listening to and jiving along with the Seventies and Eighties music. How could it be that in 2024, they even know this music that blared from my car stereo while I was still in high school? I wondered if we were stuck in time at a place where war, politics, and the bizarre deviations we experience daily in the U.S. didn’t exist. Politics in Zimbabwe are not worthy of discussion. It is a corrupt oligarchy, and no discussion is necessary. Elections do not matter; things will never change as they haven’t since the early eighties. Maybe that is why the music has never changed. There is a concept that music is tied to hegemony, in the same manner that the victor writes the history. The State prescribes what you will know and hear. Honestly, it is probably good that Zimbabweans haven’t been exposed to post-’80s American music.

Michaela knew all the words to her favorite ABBA tunes and danced along with eighties hip hop. Dean made some great moves on the “dance floor” without spilling a single drop of his iced bourbon and Coke. Then, as the Bee Gees song “Staying Alive” (an appropriate theme for safari hunting) blared from Michaela’s little blue tooth speaker, it was time for me to “put some moves down”. I am sure that I looked silly as I strutted around the dining table, mimicking John Travolta in the opening scene of Saturday Night Fever (sans the paint can), but I remained comforted by the fact that at 63, even Travolta himself probably couldn’t do much better! Plus, who will remember any of it in the morning? As the music played on, I recalled the famous words of a Sixties icon, Rod Serling; “Welcome to the Twilight Zone.”

They say Zimbabwe is a happy country. While I can’t speak for the entirety of Zimbabwe, I can say that we certainly had a happy camp. On my final hunt of the Safari, I was accompanied by Michaela, our Safari coordinator. The front seat was not for her! She rode high in the back, standing and ducking as we passed the low-hanging branches, scouting for animals. David and Adam enjoyed the cab as we traced along the Mwenezi River with our trackers. The ‘Cruiser slowed to a stop, and Adam pointed at a large male Cape baboon on the far bank. Michaela extracted my rifle for me and jacked in a cartridge while I stepped down from the ‘Cruiser. It wasn’t a long shot across the river; Adam ranged it at 150 yards. Up with sticks and down with the baboon in one shot, the whole affair took about 10 seconds. Before I could process this unanticipated event, Michaela and the trackers had stripped off their shoes and waded into the river. Wait! What about the crocodiles? By the time I had unlaced my high tops, they were already halfway across the river, transiting the exposed islands when possible. The bantering and laughing from our retrieval crew could be heard all the way. The water was only knee deep but sufficient to cover a waiting Croc, so I moved quickly, relieved to reach dry land a few feet away. We met on an island in the middle of the river, the baboon being slung between the two trackers, both wearing ear-to-ear grins. In her typical motherly fashion, Micheala directed my final photo shoot from the island in the middle of the Mwenezi River. “Christapha’! Remove your hat and stand over here. Hold his head up and…Smile!” I followed orders directly but declined the manipulation necessary to expose the baboons' massive canine teeth. After all, we have trackers for that. And so, it appears that baboons cannot read our minds, at least not at 150 yards.

Last Day of the Hunt on the Mwenezi River

Happy camp? Yes. By now, I felt young again, as if stepping back by forty years when my best times were found on the banks of the Platte River in Nebraska, hoisting catfish with my buddies and drowning our thirst with a Falstaff. Now, we were on the bank of the Mwenezi River, a mirror image of the Platte, celebrating my last day on safari with a cold Zambezi. The circle was now complete, and it had enclosed me along with my friends, old and new. My thirst for Africa was sated, and I was reborn.

The Nuanetsi

There can be no overstating the quality of hunting in the Nuanetsi Conservancy. Each hunter in our five-person group found their trophies, though collecting them was an occasional problem. The PHs finished the Leopard hunt, and one wounded buffalo was never found. These unfortunate events were not the consequences of the location, our PHs, or any factor other than the vagaries of hunting in Africa. However, Lou’s book “In the Salt” describes his former days as a Cape Buffalo culler. Between him and his three friends, 600 buffalo were culled. The average number of rounds expended was 3.6 per animal. Two of the crew of four used cartridges in the over .400 class, while the other two were shooting .375. On average, it would seem that a Cape Buffalo needs to be “wounded” three times before it can be killed. I hear elephants can be similar. Though I cannot state from whom this quote came, it is nevertheless an essential aspect of safari; “Learn to shoot before you come to Africa,” and I would add- be above average.

Map of Nuanetsi Game Ranch in Zimbabwe

Our success was also partly due to timing. September in Zimbabwe is the tail end of the winter or the beginning of spring. The deciduous trees are mostly bare, and only patches of green grass remain. Annoying bugs are absent, and the days are pleasant in the open sun, if not a tad hot. It is easy to spot and stalk in most areas due to the sparsity of foliage. Of course, the inverse is valid for the animals we sought, so a cautious approach is always needed. The road and trails are dry and powdery, making tracking fairly easy. Knowing that the habits of our prey are oriented around food and water, conditions are ideal for locating game. From my perspective, the most crucial feature of the Nuanetsi is the labyrinth of water holes and impoundments. As a remnant of the former cattle ranching days, these water features are fed mainly by a network of pipelines extending from various wells. Dams form the larger impoundments and still hold some water from the previous rainy season.

This water network is under the continual care and maintenance of a fellow I knew only as the “Bicycle Man.” His tracks could be seen snaking about various roads and trails as he stops to check water levels and look for line breaks. Occasionally, we would see him far ahead as he spun down a lonely road on his single-speed rigid-frame mountain bike. One can only imagine the athleticism of this fellow. Aside from the sheer number of miles he covered, he was almost impossible to catch, given the limitations of our leaf-sprung Landcruiser. On one occasion, we crossed paths as he did a minor pipeline repair. In the fashion typical of the Zimbabwean natives, we were met with a broad smile and hearty hello spoken in Shona. Here was this man with only rudimentary tools to conduct the needed repairs. He carried no water, food, or device he could use for protection. Perhaps the strange appearance of the bicycle itself was sufficient to abate the interest of Lions? Lou offered him an apple and a long swig from his canteen. I sensed that he was neither fearless nor ignorant, as those two qualities are sure ways to end your tenure in Africa. He obviously possessed a durable intelligence and measured respect for his surroundings, which were handed down to him through experience and tradition. Of the many memories I collected in Zimbabwe, those of the Bicycle Man surpassed anything I could understand.

In the dry season, the various water features become focal points for activity as tracks extend from and to the ponds like circuits on a breadboard. Reviewing the tracks near a pond can be an excellent way to begin the day. Combined with knowledge of the nearby flora, a plan can be formulated. This is essentially how we conducted our successful Kudu hunt. Lou highlighted this method by adding one extra bit of information. We had found a location nearby a water feature that still possessed a good stand of somewhat green grass. This information suggested an excellent location for either Zebra or Cape Buffalo. We stopped at an intersection to review the tracks but found none from Zebra. However, there were plenty of those of Cape Buffalo and some very fresh lion tracks. Lou made a call; Buffalo are nearby; in fact, quite close. We loaded up and continued on our way, and in not more than fifty yards, we spooked a small group of Dagga Boys. As I was to learn, lions prefer Cape Buffalo meat and will often be not far from the herd. After the sighting, Lou radioed Tanya, who was on a quest for Cape Buffalo, and we departed the area, leaving it for Tanya and Monte.

A First Timer

Typically, safari planning begins at least a year in advance, maybe two. Though it is possible to go as a “lone wolf,” the advantages of having a few other victims, or friends, in camp cannot be understated. Be careful who you choose. I have declined some amazing adventures in the past because I did not know everyone involved, and I am glad I did. However, you can distribute the costs and tribulations evenly with several hunters. I have known David for several years, and even though we can only meet occasionally, we have found time to complete a few short adventures of our own. My Texas friend offered the invitation during our last visit to his Colorado cabin. They had a spot for a Plains game hunter. Unwilling to make a snap decision, I deferred to the old standard; “I’ll think about it.” David left me with these final words, which cut into my soul; “If not now, then when?” I thought long and hard and contemplated a good answer to his question. At my age, “when” may never come, and “Now” was as sure as it could be. I called the next day to accept.

The truth is, I know of no man who hunts who has not dreamed of hunting in Africa. For most of us, it seems like “A bridge too far.” But now I was standing at the foot of the bridge. I had 2-1/2 months before “wheels up”. It was doable. My first contact was with Debbie at Gracie Travel, followed shortly after that by Michaela Adams at Far and Wild. Things were rolling as my wife took over the travel portion.

Among other things, I needed a new rifle. Although I have several, none were quite right for Africa. So, the first order of the day was to procure a proper rifle. The Ruger Hawkeye series has several that were purpose-built for Africa. Since I had recently had shoulder surgery, I opted for a 30.06, supposedly adequate for use on all plains game in Africa, though not highly recommended for some. Yes, adequate. Try telling your wife or girlfriend that she is adequate. Do you really want an “adequate” rifle for hunting? Looking back, I should have stepped up a caliber or two. After my Zebra fiasco Lou had only three words of advice; “Bring Enough Gun”. Translated, this means bringing the largest caliber you can shoot effectively. His favorite Plains game caliber is the .375 H&H, though he packs a .338 for backup. The .375 can cross into the dangerous game arena, but Lou says it is not ideal for some larger animals. However, the extra “branch busting” and shocking power of these two cartridges may save you from a half day long tracking session. Heck, even Michaela shoots a .375. And what is it to shoot effectively? Ahh, the nuances of words can get you lost. Where we were hunting, a 100-yard shot is quite possible, and longer shots are rare but not preferred. The exception was the baboon on the river. A three-inch group at 100 yards from the bench seems a reasonable minimum standard. If that is not possible, perhaps abstract art may be a better preoccupation for the would-be hunter. Then, whatever is put on the paper won’t cause so much distress.

My Friend Lou

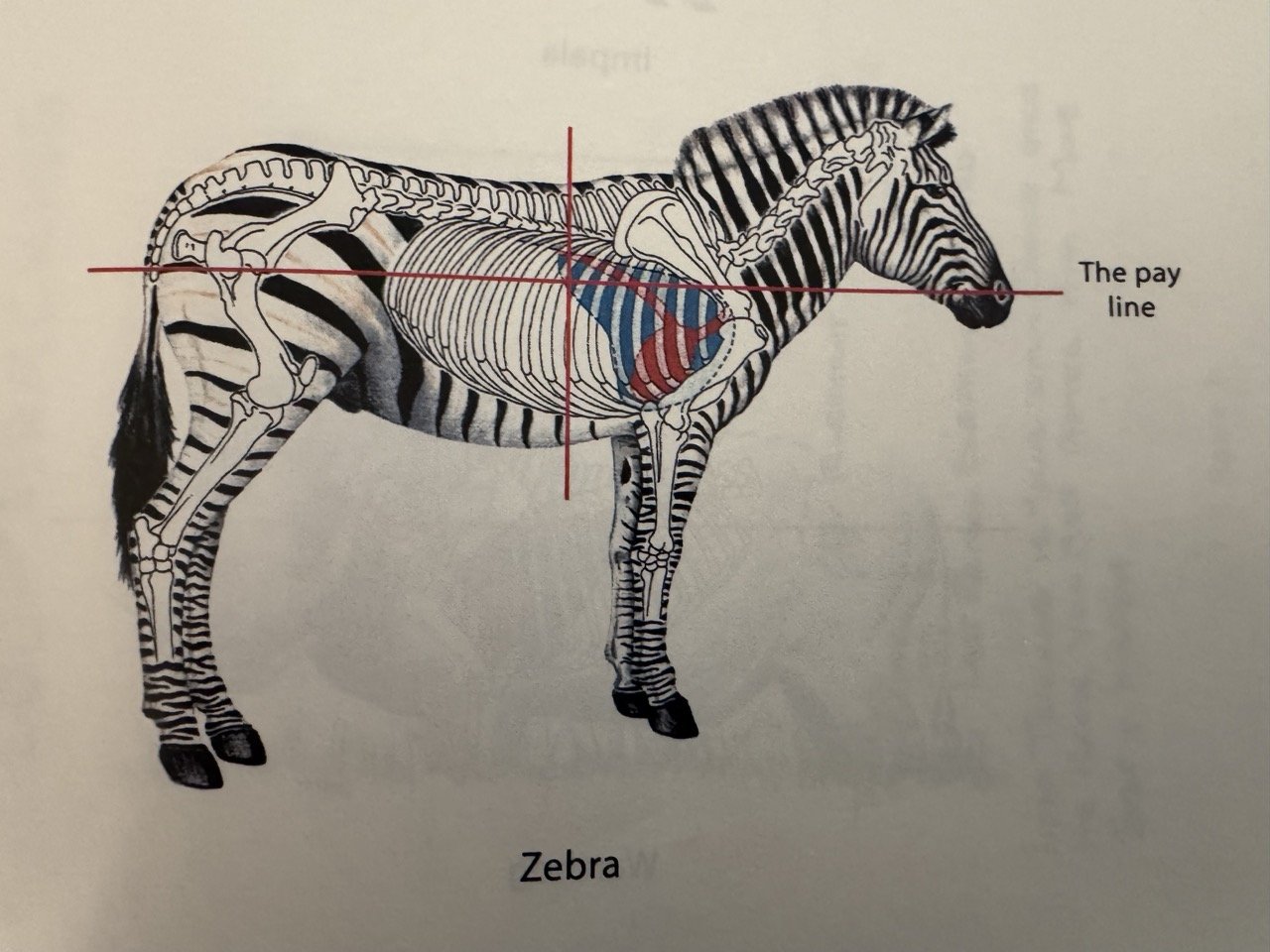

I read all I could find about African hunting. I binge-watched YouTube safari videos, especially those of African Jack, our videographer, and spent some time at websites like AfricaHunting.com. I made a list and went on a shopping spree. But as I would find out, about half of what I heard was nothing but bravado wrapped in Cape Buffalo excrement. If you want it straight from the horse’s mouth, Lou Hallamore wrote the book on African hunting, actually two: In the Salt and Chui! I procured a copy of the former; however, his books are rare and becoming quite valuable. My copy will be all the more useful to me as he kindly commemorated our trip on the inside front cover. In The Salt begins with a history of the Rhodesian War that led to the transition into Zimbabwe. At 81 years old Lou has seen it all, including being decorated for service in the Rhodesian Army, where “two-legged” safaris were common. He is a renowned Leopard hunter (read his book Chui!) and has killed more Cape Buffalo than anyone that has walked this planet. The book continues, in textbook style, with descriptions of the game species, vital zones, and diagrams depicting the latter. He writes about the pay line; it was good to know the pay line before I stepped into the bush! Hint: you pay no matter what side of the line you hit.

Payline on a Zebra from Lou Hallamore’s book “In The Salt”.

Quite frankly, I was intimidated by the prospect of having Lou Hallamore as my PH. He is a true legend, and I expected the man to be hardened by years in the bush or on the hunt for two-legged prey while trying to preserve the former State of Rhodesia. Would a man like this be dismissive towards a first-time hunter, or would his reaction be scathing as I stumbled about? Like everything about Africa, I would be surprised. Mistakes were met with a knowing smile and an occasional bit of guidance. The “machine” that our group became was his doing. The only minor irritation I detected was my seeming inability to close the Landcruiser door quietly. After a few reminders and piercing stares from the trackers, I broke that crass American habit. But when Lou spoke, I listened; wisdom like his is parsed like bits of gold plucked from a stream bed. As it would turn out, we had 10 days of fun and only a few moments in the ‘Cruiser interrupted by silence. With our mutual interest in hunting, fishing, and World affairs, there was always something to discuss or laugh about. When not discussing the intricacies of a particular game species, Lou easily digressed to history, politics, and personalities. His opinions are not for the shy, nor should they be. Punctuated by occasional one-syllable words, I received a master course on Zimbabwe, politics, people and African game. At his age, Lou hunts smart, and though I know he was not pleased with our long chases after the wounded animals, it all ended with a smile and a hearty handshake. I could not have asked for a better mentor for my first time afield in Africa.

Safari Mates

For my first Safari, I was privileged to have the company of four experienced Safari Hunters. Though I have enjoyed getting to know David Barlett through several previous venues, the Safari schedule left only the evenings and our bits of time between travel legs to become more acquainted with my other fellows. But I can say that David knows how to pick a crew.

Shannon, Michaela, David, African Jack (Jean), Hersell, and me (Chris).

On our first night in Bulawayo, Hershell and I shared a few beers and quite a bit of philosophy. Hershell, a professional civil engineer, has applied his keen mind to the analysis of all things Biblical. He speaks of his favorite subject not in the style of a preacher but as that of a historical scholar. Quoting chapter and verse, he has blended ideas and verses from both the Old and New Testaments into new thought forms, offering insights I had never considered. Like the rest of our company, he was calm and collected on the hunt or not. Plus, he is also the only one in our group to have achieved YouTube stardom during a previous hunt with Tanya Blake. His foray for a leopard turned into some real excitement, and his Sable is a truly beautiful trophy.

Monte appears as the patriarch of our camp. His calm and unflappable nature has been perfected from years as a litigation attorney. I listened when he recounted his successful elephant hunt during the first week of safari. The story, mixing humor with the terrifying scene of a charging elephant, left me weak-kneed and a little queezy. He is a big fan of Blaser firearms, and after hearing the story about the elephant hunt, I can see why. In my imagination, I could see him racking the straight pull action of his rifle as he emptied his magazine into the charging bull elephant. Then, with the giant beast lying at his feet, smoke still rising from the muzzle and a small pile of brass a few feet to his right, he extracts a neatly folded handkerchief from his breast pocket only to dab the single bead of sweat from his brow. I think that is how his story went.

Shannon is a pleasant and approachable man, but at well over six feet, with a razor-hewn look, he is physically imposing, looking more like a Special Forces operator than a CEO. Dressed in Safari style and carrying a rifle, he would cause you to do a double take. With a Master’s Degree in Chemical Engineering, his fellow engineers, Hershell and I, found it appropriate to bow down whenever he entered the room. Shannon collected several trophies, including waterbuck, wildebeest, and a massive crocodile that will soon be a fine pair of boots, or two or ten.

Our Fearless Leader, David

And last but far from least is our fearless leader, David. Though originally from Arkansas, he is thoroughly Texan. His demeanor appears to be a combination of Matt Dillon and Doc Holiday. A tall, easy-going man, he is cool under fire but ready with a quip at a moment's notice. I could go on and on about David but would instead refer to the books and passages he has written. His style of writing is authentic to his true nature. I first encountered David online as we discussed and traded parts for a type of old Safari vehicle. Meeting in such a manner is not mere chance; I am convinced that divine intervention played a hand. It is through him that I was able to participate in this dream of a lifetime. I have read all of his books, but my favorite was “Zimbabwe Elephant Hunt 2008”. Therein, he digs deep into his studies of ballistic performance on African game. During this hunt, as with all of his hunts, the crew collected all recoverable bullets for his ongoing study. His choice for this hunt was Northfork monolithic copper bullets that he had hand-loaded. He thoughtfully prepared a box of 200 grain 30-06 for me as well.

The Trackers

As trackers often are, Clement and Takesure were unsung heroes of this safari. Truly, there could be no hunt without them. Takesure appeared to be in his twenties, but he moved with confidence, belying his age. Our point man, Clement, is the old wise man, and judging from the grey tinge at the tips of his short hair, he may be in his fifties. As much as I tried, my Western eyes could not see as they did. While tracking, Clement and Takesure used hand signals and only occasionally stopped to collaborate. As always, I stayed close to Takesure, watching his every move. Now and then he would point to a particular track or sign. He did so for no reason other than to communicate to me the importance of what he saw. When tracking the Impala, he would lift a pinch from the ground and smell it. I found out later he was trying to determine where the Impala had been shot. There was no time to stop during these moments, so I tried to glean what I could. The particular tracks they pointed to suggested a change in direction or speed; at least, that is what I surmised. Broken branches, blood and scat complemented the story as our hunt was played out on a massive board. In my readings of American history only a few names come to mind that could compare: Bridger, Boone, or Crockett.

It was so apparent that they enjoyed every moment of the hunt and honestly shared in every success and failure. I felt more obligation to them at times than anything else. After each kill, their bright eyes and beaming smiles revealed their true pleasure. It was obvious that they already possessed the very thing that I sought from this experience in the bush: a primal and simple joy of hunting. Late in the afternoon, as my two weeks were coming to an end, we headed out for a francolin hunt. With a bolt action .22 sitting in my lap and a cold beer in my hand, we meandered around, picking off the little grouse. Though not hard to hit, I did somehow “wing” one, and it took off like a scared cottontail. Takesure and Clement peeled out after them, laughing and smiling as they ran around and around after the wounded bird. I so wanted to join them in the pursuit but my old knees precluded anything more than a brisk jog. The scene was similar while wing-shooting for Dove. I wished that I could have been a better shot, just to keep my Shona friends smiling. However, I am sure they enjoyed their freshly roasted grouse and dove that evening in their camp. On the last day, before their departure, I was pleased to give each of my crew a cash tip. Money, though tangible and useful, is a transitory commodity. I also left Takesure with my favorite multi-tool, and Clement received a skinning knife. I wanted something for them that was long-lasting and durable, like the memories they gave me during my time in the African bush.

The Meaning of Safari

Last Night of Safari Under the Baobab Tree

As I close out the “memoirs” of my time on Safari, I must write about something that I am still trying to understand and will endeavor to put it into words.

I observed my hunting partners throughout our days there. How did it feel for them to kill an elephant, to be charged by a Cape Buffalo, or collect a beautiful horned trophy? Only they knew, but I did watch them closely and listened as they spoke. As they passed by, I observed their faces and especially their eyes. It was odd, almost as if they had been drugged. Their stare was not vacant; it was peaceful and deep, if it was anything. There was something in the air, if not for real, then metaphorically at least. David, the only one there that I knew fairly well, I watched keenly. At first, I thought he seemed bored, and I even suggested to him that, as an old safari hunter, he might be becoming a little jaded. I could not have been more wrong.

My initial perspective of an African Safari was that it is a grand party for big boys with expensive vintage rifles, period-correct costumes, and the finest aged distillates. That is how it appears from an outside observer and how it is often portrayed. And it can be all that, but that is not all it is. For our final night on Safari, our camp moved to a spot beneath a giant Baobab tree to soak in our last moments. David sat in the ring of chairs, quietly contemplating a hefty Churchill. He was not the usual gregarious fellow, and I thought perhaps he was sad that it was over. Later, I sent a video of our final night as a group text. David’s reply provided me with the insight I was looking for. He said, “Chris, outside of my faith and family, you have captured me in a moment where I am most content, comfortable, and at peace; thank you.” No. Thank you, David.

Baobab Tree

Safari is a Swahili word meaning Journey. If, by chance, one thinks it means traveling to or through Africa, they certainly do not know what Safari is. Africa is the place for the journey and nothing more. We experience many journeys through careers, marriage, children, and finding the true meaning of life through love, faith, and giving. And as such, those journeys prove their purpose. African Safari is a personal journey, unfettered by the other trappings of life. It is for you and you alone...a most selfish but necessary endeavor. Each day it felt as though I was stripping away another layer of who I thought I was and starting to see who I really am. My failures washed away any pretenses I had of my abilities. I can shoot well and thought that would be enough until I found myself, butt squarely planted on my heels, while trying to take a shot through a two-foot-wide gap in the bush; or chasing wounded animals for hours on end. Good shot placement is just a start. In Africa, I had to relearn how to hunt, which can only be accomplished by starting from scratch. Expect to be humbled and to become that boy again, but anticipate learning so much.

Becoming an African hunter is a journey. It begins with knowing that virtually every animal here would try to kill you, given the chance (it’s the ones that you don’t see that succeed). That is strangely the most beautiful part of hunting in Africa. Being the hunter is part of the game, as is being the hunted. Dangerous game hunters know this all too well as do the PH’s. On the very day we departed back to Bulawayo, a Zimbabwe born PH was attacked by a wounded Cape Buffalo in nearby Zambia. In the same manner that the buffalo dispatch lions the man was hooked and tossed three times before being trampled. He died on the flight to the nearest hospital. There were no smiles in Africa on that day.

It became apparent that my entire experience in Africa, as rich as it was, had so much more to offer. The artificiality of how we hunted: the trackers, guns, PH’s, rules of engagement, and even the camp itself left closed chapters of the actual truth. I believe that our trackers know it innately. How could they not? Their ancestors wrote the book. I visualized a time when they did as we did with nothing more than a breach cloth and spear. The point is clear: without the tether of civilization holding us back, we could very likely have met an untimely demise in this place. But it is a tether held loosely; tug away at your peril! And, by the way, using a flashlight at night while traversing camp is not just a friendly tip; it is a survival tactic.

To me, Africa is not just a place or a geography; it feels alive with an intelligence of its own, communicated through mysteries to be observed each day. I heard an interesting anecdote regarding the moon seeming so different here; some are not sure it is the same moon as seen elsewhere in the world. A Western mind would scoff at such a thought. But somehow, it appeared closer than any place I have ever been. Every detail on the massive orb can be observed with the naked eye, and the color is a rich orange and yellow. Yes, the stars were bigger and brighter, too. When you see a lion staring you down from 200 yards, you feel it to your core and realize he knows something about you that you don’t want to know! As with all of the wild encounters, it’s personal. On the trip back after our last night at the baobab tree, the fricking elephants had left a parting gift; a very large tree blocked our way back to camp. It made me smile and gave a dozen slightly inebriated partygoers a reminder of our days hacking, pulling, and maneuvering. Those beautiful animals met us at the gate as we departed the Nuanetse the next day, just as I knew they would. They didn’t want us to leave. And I did not want to.

The African Moon

While I stood on the bank of the Mwenezi River during my last day of the hunt, those times along the Platte really did come flooding back as if a secret door had been unlocked or I stepped into some strange vortex. I was truly surprised. Earlier, while still in Colorado, as I began my preparations for the hunt, a feeling swept over me that I hadn’t had since I was a young fellow of twelve standing in the cold and dark, shotgun in hand, on the edge of a frost-covered field. I tried to hold onto that moment, studying it as it slowly slipped away. Any hunter remembers those moments, but can they still feel it? Africa is the venue, and hunting is the catalyst for bringing back those feelings. It is Safari in the grandest sense. After months of preparation and two weeks in Africa, it is time to let these memories find their home deep within me. But they will always be there waiting to be reawakened during my next Safari, wherever and whatever that may be.

Back Home

The Colorado Elk season approaches as I sit here at home, trying to collect my memories of two weeks in the African bush before they fade. By this time next week, I will be hiking around at 10,000 feet, pursuing my favorite American game. Will I be a better hunter because of my experiences in the bush? Maybe, but I will recall the wisdom and the tactics we used. I will remember Takesure, as his bright white eyes pierced through me at each misstep, and I will make every endeavor to ensure that does not happen while I traverse the spruce-covered mountainsides in my hunting area. I always fancied being a decent tracker, but now I know what real tracking is. Can I put these lessons to use? Hopefully, but there is one thing for certain though; unless I run into another African hunter, my campfire stories will be rich and unparalleled.

Our Kudu Trophy

I recall the Zimbabwean use of the word “Magic”. It is often used as a preface when meeting a friend or discussing something fortuitous. In our Western culture, we might think of it as “divine intervention” or “luck,” but I have yet to fully grasp the Zimbabwean concept of Magic. After two weeks in the bush, hunting and viewing a spectacular array of animals, soaking in hours along the Mwenezi River, and enjoying the ever-bright personalities I spent time with, I think I have some idea. I know that in Zimbabwe, Magic is what puts a smile on the face of every person I met. It gives perspective to the past and the future. It is behind every laugh and every plan. It is the color of the Sun and the Moon and what can turn any moment into a spectacular one. And Magic is all that is left in a person when they are subsumed into the African bush to become both the hunter and the hunted. Back home now, I carry some of that Magic with me. For me, Magic means that nothing will ever be the same….and that’s a good thing.